Ricardo, over at Extra Fine Writing, asks the question “Does anyone actually use a pen to write a novel?”

When I hear that some famous author drafts their novels with a fountain pen, or when I see that in film or TV as a visual trope, my immediate instinct is to absolutely believe that they are lying.…

Do any of you actually do this?

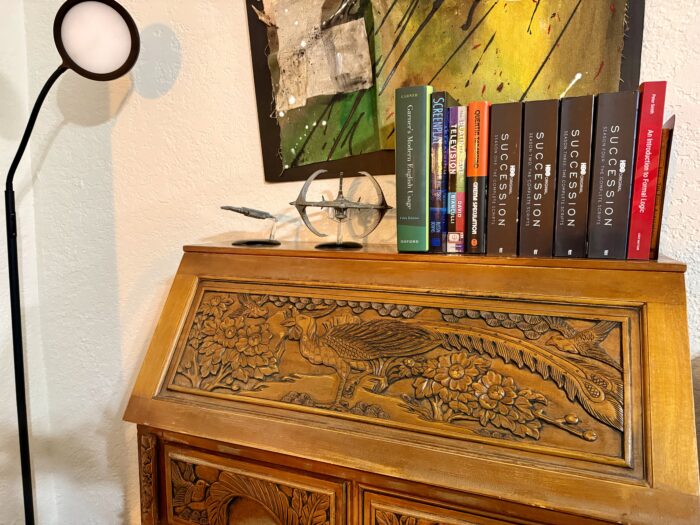

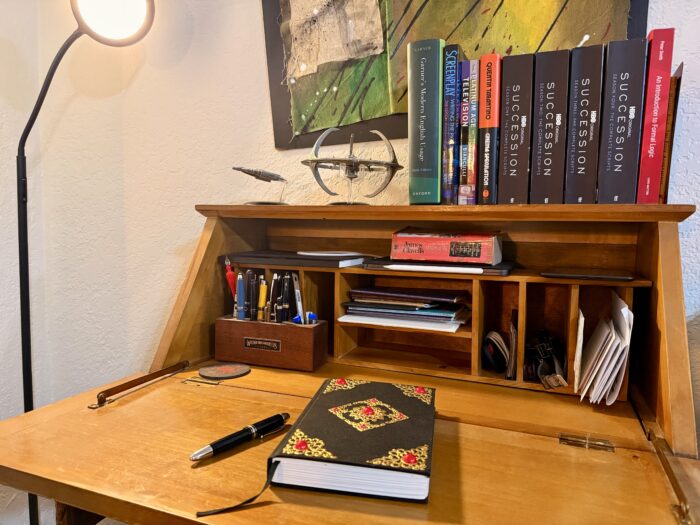

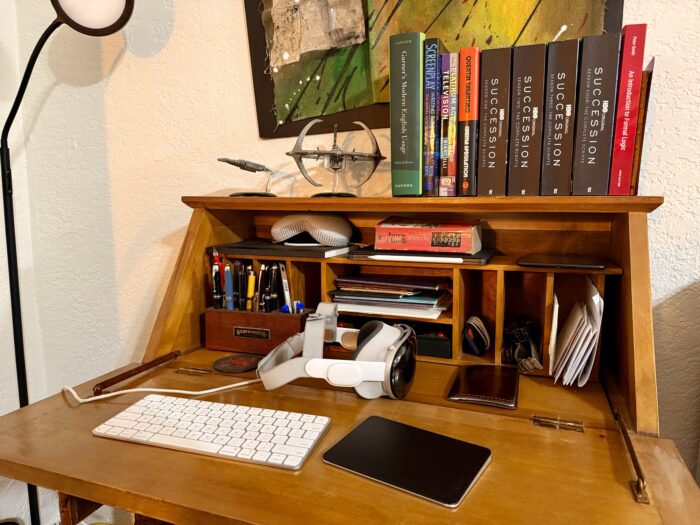

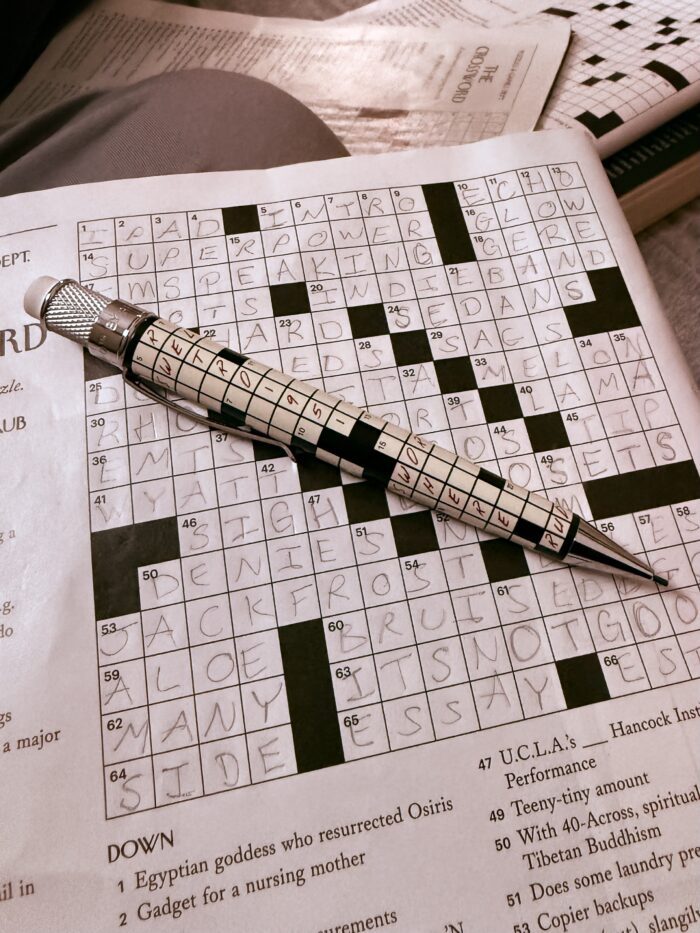

Like, do you sit down with an unlined, blank piece of paper and start writing the first line of a novel, longhand, perhaps at an ornate desk in front of a fireplace? Do you crumple it up and throw it out when you don’t like what you’ve written and start over with a fresh sheet, because you have an endless supply of both time and paper?

I do. Of the seven novels I’ve had published in the last twelve years, one of them, The Assured Expectations of Things Hope For, was first-drafted entirely by hand. Granted, it’s probably my shortest book, at only around 17,000 words. But about a month ago I finished a new novel, also entirely first-drafted longhand, with a fountain pen (mostly a Pilot Custom 823), and I intend to write long-form prose this way for the rest of my life (although the pen, at least for the foreseeable future, will be the exquisite Montblanc Meisterstück 149 100th Anniversary Edition I recently acquired).

Ricardo writes:

I did use pens—and used them heavily—to plan, organize, and manage the work. I used them for creating characters, connecting plot points, doing research, laying out timelines, making to-do lists for revisions and edits, sketching cover designs, and so on. I have pages and pages and pages of this stuff; some days this was all I did. Literally everything related to the book except actually writing it was done by hand, because that was heavy-duty, nonlinear thinking work that benefited from slowing down.

Actually drafting the book, though? I like the idea of doing this by hand a lot, but I gave up after a couple days of trying. It was tiring enough to do on a computer, and the computer has the benefit of a “find” feature for when you decide a character’s name is not dumb enough and change it in the middle of revisions.

I think drafting the book—that is, crafting the sentence—is the part of writing that benefits most from slowing down. Sentences should not be rushed. They should be carefully, delicately considered—“word by word,” as Verlyn Klinkenborg put it in his excellent book Several Short Sentences About Writing. Plus, more importantly than ever in this era of AI-generated slop, writing by hand allows us writers to show our work.

Of course, if you write your first draft by hand, you’re probably going to need to type it up at some point. But this is great. This is not extra, unnecessary work. This is the work, because this is where you get to make your first edits. Don’t want to type a sentence up? Then don’t type it up! Leave it out. This is where you get to make your first deletions and rewrites: in the transcription process. If you write your first draft by hand, on paper, and then transcribe your second draft, you’re likely to create a much stronger second draft than if you started at the computer in the first place.

And if you can’t bring yourself to sit down and transcribe your handwritten writing, if that sounds too exhausting, then it probably wasn’t compelling work in the first place.